|

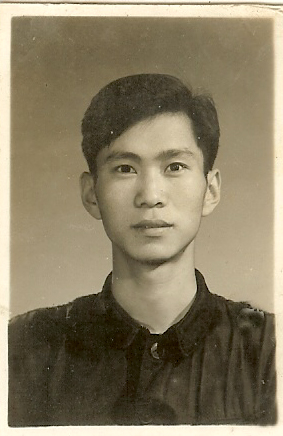

常耀信

常耀信,河北 沧州人。 毕业后留校,同时被公派去英国留学,大约一年后因“文革”中断学习,回国。 "文革”期间曾参加中国援助阿富汗和巴基斯坦工程队,任翻译。 文革后赴美国Temple University留学,获美国文学博士学位。回国后任外文系教授,副系主任,系主任,博士生导师。 定居美国关岛,任关岛大学英文系教授,同时兼任南开大学外国语学院博导。

毕业照前排左起第二人为常耀信,1965

近照

近照

|

1965

1965 |

巴基斯坦首都, 70年代中期在周总理所植友谊树前

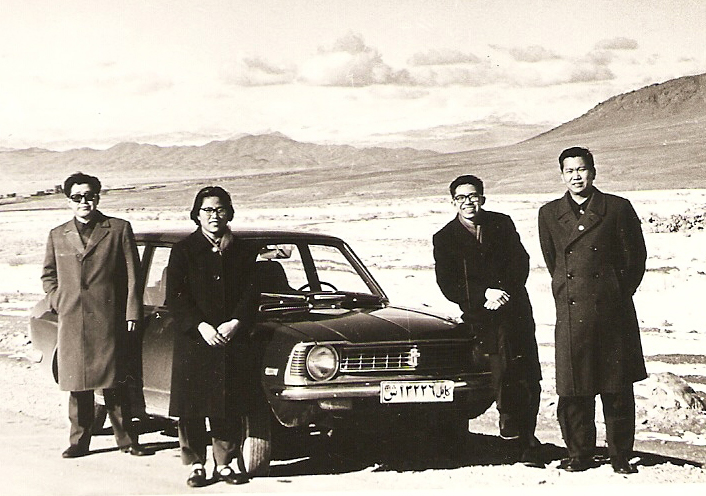

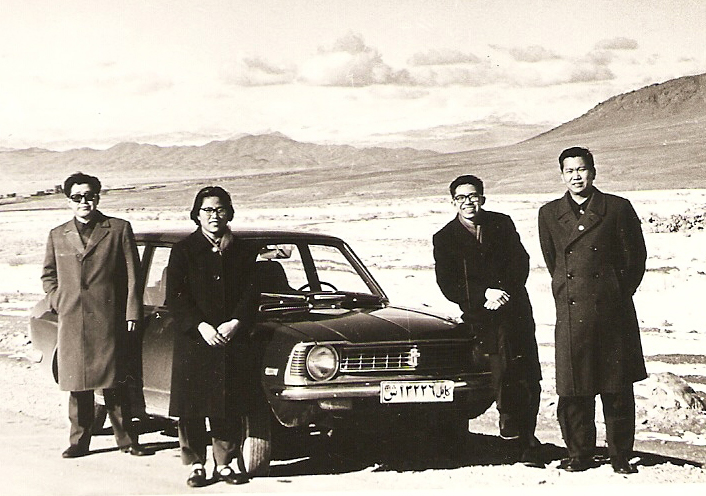

70年代中在阿富汗首都郊区

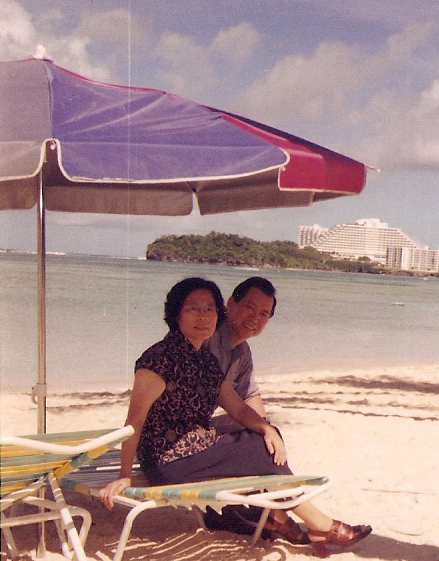

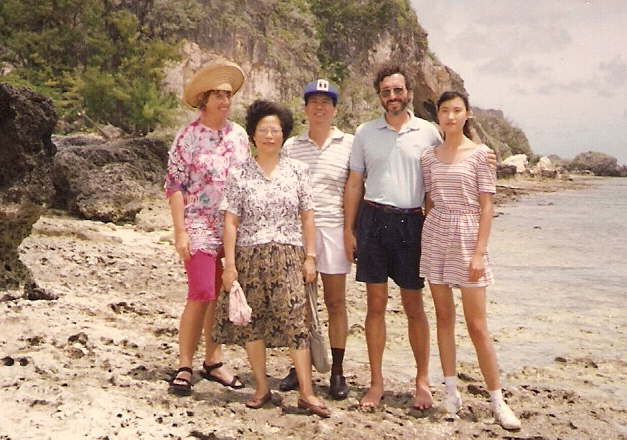

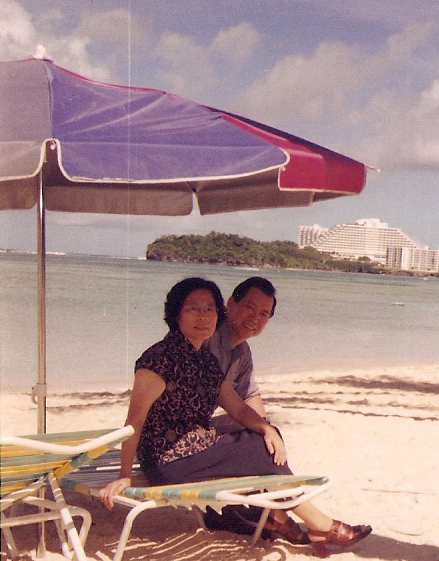

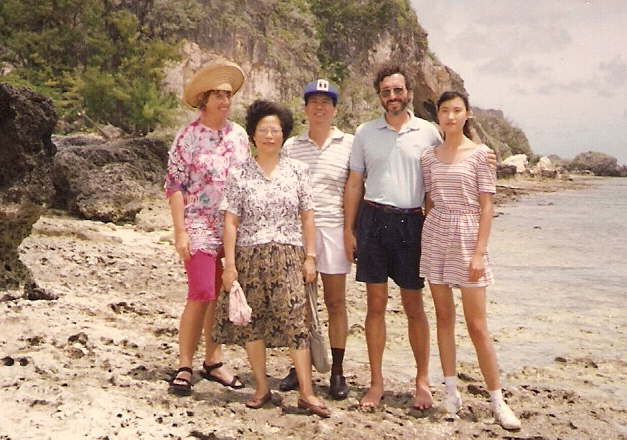

关岛, 太平洋海滨

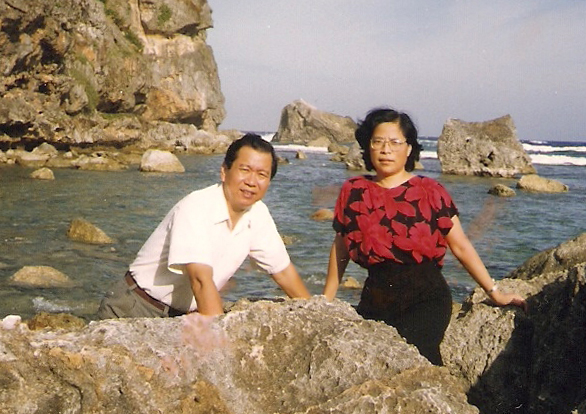

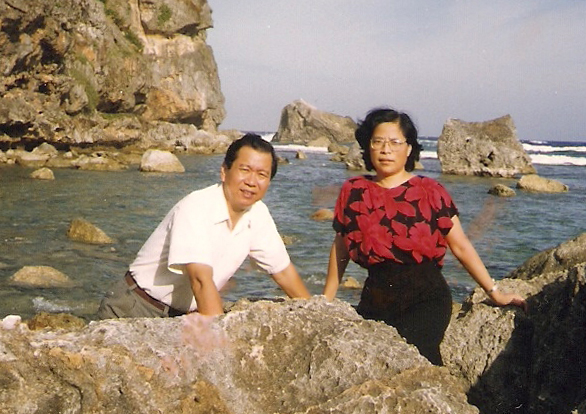

1995年在太平洋海滨

1995年在太平洋海滨

王蕴茹杨俊起常耀信,2001年7月8日于杨俊起家

|

《美国文学选读》 (上下册;主编之一)

·出版社:南开大学出版社

·页码:854 页

·出版日期:1987年

·ISBN:7310003969

|

《美国文学简史》

·出版社:南开大学出版社

·页码:654 页

·出版日期:2008年

·ISBN:9787310002900

|

《英国文学简史》

(普通高等教育十一五国家级规划教材)

·出版社:南开大学出版社

·页码:587 页

·出版日期:2008年

·ISBN:7310023986

|

《漫话英美文学》-英美文学史考研指南

·出版社:南开大学

·页码:362 页

·出版日期:2006年

·ISBN:7310020715 |

《精编美国文学教程》(中文版)

·出版社:南开大学出版社

·页码:465 页

·出版日期:2005年

·ISBN:731002169X |

《美国文学批评名著精读》(上下)

·出版社:南开大学

·页码:798 页

·出版日期:2007年

·ISBN:7310026748 |

《英国文学大花园》

·出版社:湖北长江出版集团,湖北教育出版社

·页码:262 页

·出版日期:2007年

·ISBN:9787535147257 |

相遇大师常耀信 相遇大师常耀信

常耀信妙语解读后现代主义 常耀信妙语解读后现代主义

|

|

附卓越亚马逊网常耀信简介:教授,博士生导师,任教于中国南开大学及美国关岛大学.研究方向为英美文学。著有《希腊罗马神话》、《漫话英美文学》、《美国文学简史》(英文版)、《美国文学史(上)》(中文版);主编有:

《美国文学选读》(上、下)、《美国文学研究评论选》(上、下)及《自选评论文集--文化与文学中的比较研究》等。

此外,还在国内外刊物上发表过多篇论文,阐述中国文化对美国文学的影响。1988年被选人英国国际传记中心编纂的《远东及太平洋名人录》,后亦被选入《美国名师录》。 附卓越亚马逊网常耀信简介:教授,博士生导师,任教于中国南开大学及美国关岛大学.研究方向为英美文学。著有《希腊罗马神话》、《漫话英美文学》、《美国文学简史》(英文版)、《美国文学史(上)》(中文版);主编有:

《美国文学选读》(上、下)、《美国文学研究评论选》(上、下)及《自选评论文集--文化与文学中的比较研究》等。

此外,还在国内外刊物上发表过多篇论文,阐述中国文化对美国文学的影响。1988年被选人英国国际传记中心编纂的《远东及太平洋名人录》,后亦被选入《美国名师录》。

|

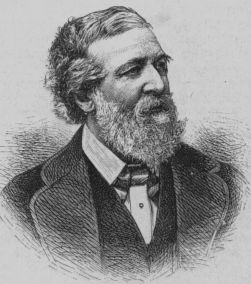

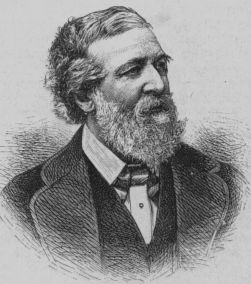

English Poet Robert Browning (1812-1889) |

Robert Browning

(This work of art is in public domain.)

Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose mastery of dramatic verse, especially dramatic monologues, made him one of the foremost Victorian poets. Browning’s fame today rests mainly on his dramatic monologues, in which the words not only convey setting and action but also reveal the speaker’s character. Unlike a soliloquy, the meaning in a Browning dramatic monologue is not what the speaker directly reveals but what he inadvertently "gives away" about himself in the process of rationalizing past actions, or "special-pleading" his case to a silent auditor in the poem. Rather than thinking out loud, the character composes a self-defense which the reader, as "juror," is challenged to see through. Browning chooses some of the most debased, extreme and even criminally psychotic characters, no doubt for the challenge of building a sympathetic case for a character who doesn't deserve one and to cause the reader to squirm at the temptation to acquit a character who may be a homicidal psychopath. One of his more sensational dramatic monologues is Porphyria's Lover. The opening lines provide a sinister setting for the macabre events that follow. It is plain that the speaker is insane, as he strangles his lover with her own hair to try and preserve for ever the moment of perfect love she has shown him.

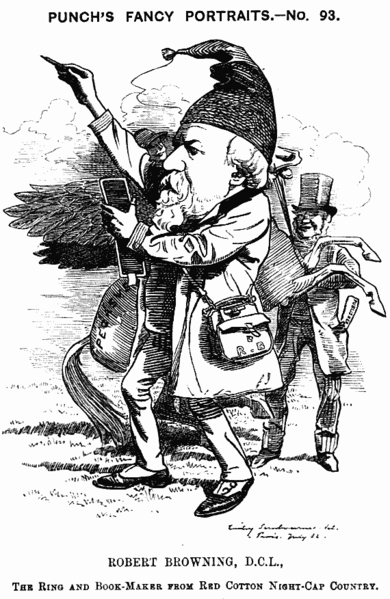

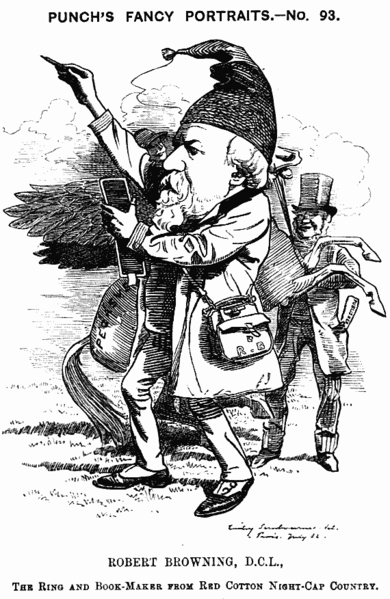

1882 Caricature from Punch. (This work of art is in public domain.)

Yet it is by carefully reading the far more sophisticated and cultivated rhetoric of the aristocratic and civilized Duke of My Last Duchess, perhaps the most frequently cited example of the poet's dramatic monologue form, that the attentive reader discovers the most horrific example of a mind totally mad despite its eloquence in expressing itself. The duchess, we learn, was murdered not because of infidelity, not because of a lack of gratitude for her position, and not, finally, because of the simple pleasures she took in common everyday occurrences. She is reduced to an object d'art in the Duke's collection of paintings and statues because the Duke equates his instructing her to behave like a duchess with "stooping," an action of which his megalomaniacal pride is incapable. In other monologues, such as Fra Lippo Lippi, Browning takes an ostensibly unsavory or immoral character and challenges us to discover the goodness, or life-affirming qualities, that often put the speaker's contemporaneous judges to shame. In The Ring and the Book Browning writes an epic-length poem in which he justifies the ways of God to humanity through twelve extended blank verse monologues spoken by the principals in a trial about a murder. These monologues greatly influenced many later poets, including T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, the latter singling out in his Cantos Browning's convoluted psychological poem about a frustrated 13-century troubadour, Sordello, as the poem he must work to distance himself from.

Ironically, Browning’s style, which seemed modern and experimental to Victorian readers, owes much to his love of the seventeenth century poems of John Donne with their abrupt openings, colloquial phrasing and irregular rhythms. But he remains too much the prophet-poet and descendant of Percy Shelley to settle for the conceits, puns, and verbal play of the Metaphysical poets of the seventeenth century. His is a modern sensibility, all too aware of the arguments against the vulnerable position of one of his simple characters, who recites: "God's in His Heaven; All's right with the world." Browning endorses such a position because he sees an immanent deity that, far from remaining in a transcendent heaven, is indivisible from temporal process, assuring that in the fullness of theological time there is ample cause for celebrating life. Browning's is assuredly at once the most incarnate and dynamic of visions of Deity, in

Christianity and perhaps in any of the world's great religions.

Home Thoughts, From Abroad

by Robert Browning

|

|

|

| |

Oh, to be in England

Now that April's there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brushwood sheaf

Round the elm-tree bole are in tiny leaf,

While the chaffinch sings on the orchard bough

In England—now!

And after April, when May follows,

And the whitethroat builds, and all the swallows!

Hark, where my blossomed pear-tree in the hedge

Leans to the field and scatters on the clover

Blossoms and dewdrops—at the bent spray's edge—

That's the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you should think he never could recapture

The first fine careless rapture!

And though the fields look rough with hoary dew,

All will be gay when noontide wakes anew

The buttercups, the little children's dower

—Far brighter than this gaudy melon-flower!

|

|

Home Thoughts, from the Sea

by Robert Browning

|

|

|

| |

Nobly, nobly Cape Saint Vincent to the North-west died away;

Sunset ran, one glorious blood-red, reeking into Cadiz Bay;

Bluish 'mid the burning water, full in face Trafalgar lay;

In the dimmest North-east distance dawned Gibraltar grand and grey;

"Here and here did England help me: how can I help England?" -say,

Whoso turns as I, this evening, turn to God to praise and pray,

While Jove's planet rises yonder, silent over Africa.

|

|

|

| |

FERRARA

That's my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Fra Pandolf's hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will't please you sit and look at her? I said

``Fra Pandolf'' by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, 'twas not

Her husband's presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess' cheek: perhaps

Fra Pandolf chanced to say ``Her mantle laps

``Over my lady's wrist too much,'' or ``Paint

``Must never hope to reproduce the faint

``Half-flush that dies along her throat:'' such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart---how shall I say?---too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate'er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, 'twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace---all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men,---good! but thanked

Somehow---I know not how---as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody's gift. Who'd stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech---(which I have not)---to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, ``Just this

``Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

``Or there exceed the mark''---and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

---E'en then would be some stooping; and I choose

Never to stoop. Oh sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene'er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will't please you rise? We'll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master's known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter's self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we'll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

** The poem is based on incidens in the life of Alfonso II, Duke of Ferrara in Italy, whose first wife, Lucrezia, a young girl, died in 1561, after three years of marriage. Following her death, the Duke negotiated through an agent to marry a niece of the Count of Tyrol. Browning represents the Duke as addressing this agent.

**********************************

|

|

Memorabilia

by Robert Browning

|

|

|

| |

I.

Ah, did you once see Shelley plain,

And did he stop and speak to you

And did you speak to him again?

How strange it seems and new!

II.

But you were living before that,

And also you are living after;

And the memory I started at---

My starting moves your laughter.

III.

I crossed a moor, with a name of its own

And a certain use in the world no doubt,

Yet a hand's-breadth of it shines alone

'Mid the blank miles round about:

IV.

For there I picked up on the heather

And there I put inside my breast

A moulted feather, an eagle-feather!

Well, I forget the rest.

|

|

My Star

By Robert Browning

|

|

|

| |

All, that I know

Of a certain star

Is, it can throw

(Like the angled spar)

Now a dart of red,

Now a dart of blue

Till my friends have said

They would fain see, too,

My star that dartles the red and the blue!

Then it stops like a bird; like a flower, hangs furled:

They must solace themselves with the Saturn above it.

What matter to me if their star is a world?

Mine has opened its soul to me; therefore I love it.

|

|

Women And Roses

by Robert Browning

|

|

|

| |

I.

I dream of a red-rose tree.

And which of its roses three

Is the dearest rose to me?

II.

Round and round, like a dance of snow

In a dazzling drift, as its guardians, go

Floating the women faded for ages,

Sculptured in stone, on the poet's pages.

Then follow women fresh and gay,

Living and loving and loved to-day.

Last, in the rear, flee the multitude of maidens,

Beauties yet unborn. And all, to one cadence,

They circle their rose on my rose tree.

III.

Dear rose, thy term is reached,

Thy leaf hangs loose and bleached:

Bees pass it unimpeached.

IV.

Stay then, stoop, since I cannot climb,

You, great shapes of the antique time!

How shall I fix you, fire you, freeze you,

Break my heart at your feet to please you?

Oh, to possess and be possessed!

Hearts that beat 'neath each pallid breast!

Once but of love, the poesy, the passion,

Drink but once and die!---In vain, the same fashion,

They circle their rose on my rose tree.

V.

Dear rose, thy joy's undimmed,

Thy cup is ruby-rimmed,

Thy cup's heart nectar-brimmed.

VI.

Deep, as drops from a statue's plinth

The bee sucked in by the hyacinth,

So will I bury me while burning,

Quench like him at a plunge my yearning,

Eyes in your eyes, lips on your lips!

Fold me fast where the cincture slips,

Prison all my soul in eternities of pleasure,

Girdle me for once! But no---the old measure,

They circle their rose on my rose tree.

VII.

Dear rose without a thorn,

Thy bud's the babe unborn:

First streak of a new morn.

VIII.

Wings, lend wings for the cold, the clear!

What is far conquers what is near.

Roses will bloom nor want beholders,

Sprung from the dust where our flesh moulders.

What shall arrive with the cycle's change?

A novel grace and a beauty strange.

I will make an Eve, be the artist that began her,

Shaped her to his mind!---Alas! in like manner

They circle their rose on my rose tree.

|

|

Night and Morning

by Robert Browning

|

|

|

| |

I.

The grey sea and the long black land;

And the yellow half-moon large and low;

And the startled little waves that leap

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,

As I gain the cove with pushing prow,

And quench its speed i' the slushy sand.

II.

Then a mile of warm sea-scented beach;

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch

And blue spurt of a lighted match,

And a voice less loud, thro' its joys and fears,

Than the two hearts beating each to each!

|

Round the cape of a sudden came the sea,

And the sun looked over the mountain's rim:

And straight was a path of gold for him,

And the need of a world of men for me.

|

|

|

|

|

|

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()